Literary Britain takes its first trip to distant shores

I had long wanted to travel to Dublin. I’ve visited Europe frequently but, for some reason, had ignored the vibrant European capital on our sister island to the west. Dublin’s status in literary history is legendary, and the number of poets and novelists the city has nurtured is astonishing. Literature runs through Dublin’s veins like Guinness, and the city actively celebrates its literary heritage through museums, galleries, libraries, and pubs. One of the masterpieces of world literature is set on the streets of Dublin, so it’s no surprise the city is proud of its status and eager to show it off.

We arrived early on a spring morning, having caught the 8:00 a.m. flight from London—a course of action that entailed a 4:00 a.m. start. The flight, and the Dublin transport network, were quick and efficient. Having checked into our hotel, we set off to explore the city. I had brought a couple of friends along on this trip. Emma has been my traveling companion for a number of years, and as she and her partner, Matt, are expecting a baby soon, I thought this might be our last opportunity for literary tourism—for a little while, at least.

Our first stop was the Seamus Heaney Exhibition run by the Bank of Ireland in their building on Westmoreland Street, in the heart of the city. This was a well-curated exhibition, with mementoes and notebooks of the great man, along with displays based on his poetry. It served as a good introduction to Irish literature, as we had all encountered his work before. Much of it appears on English school reading lists for GCSE, and I had taught a great deal of it myself in the past.

Seeking refreshment, I embarked on the first of many pub visits. The Palace Bar has remembrances of the many literary greats it has served over the years: Patrick Kavanagh, Seamus Heaney, Samuel Beckett, Brendan Behan, and, of course, James Joyce. The interior is unspoiled and Victorian, with dark wood and polished brass and a comfortable lounge area. And yes, the Guinness really is better in Dublin. I don’t drink it much in London, as it tends to be too cold and tastes stale to me. In the Palace Bar, it was fresh and nicely chilled. We drank and chatted in the back room while Dublin’s literary greats looked down on us.

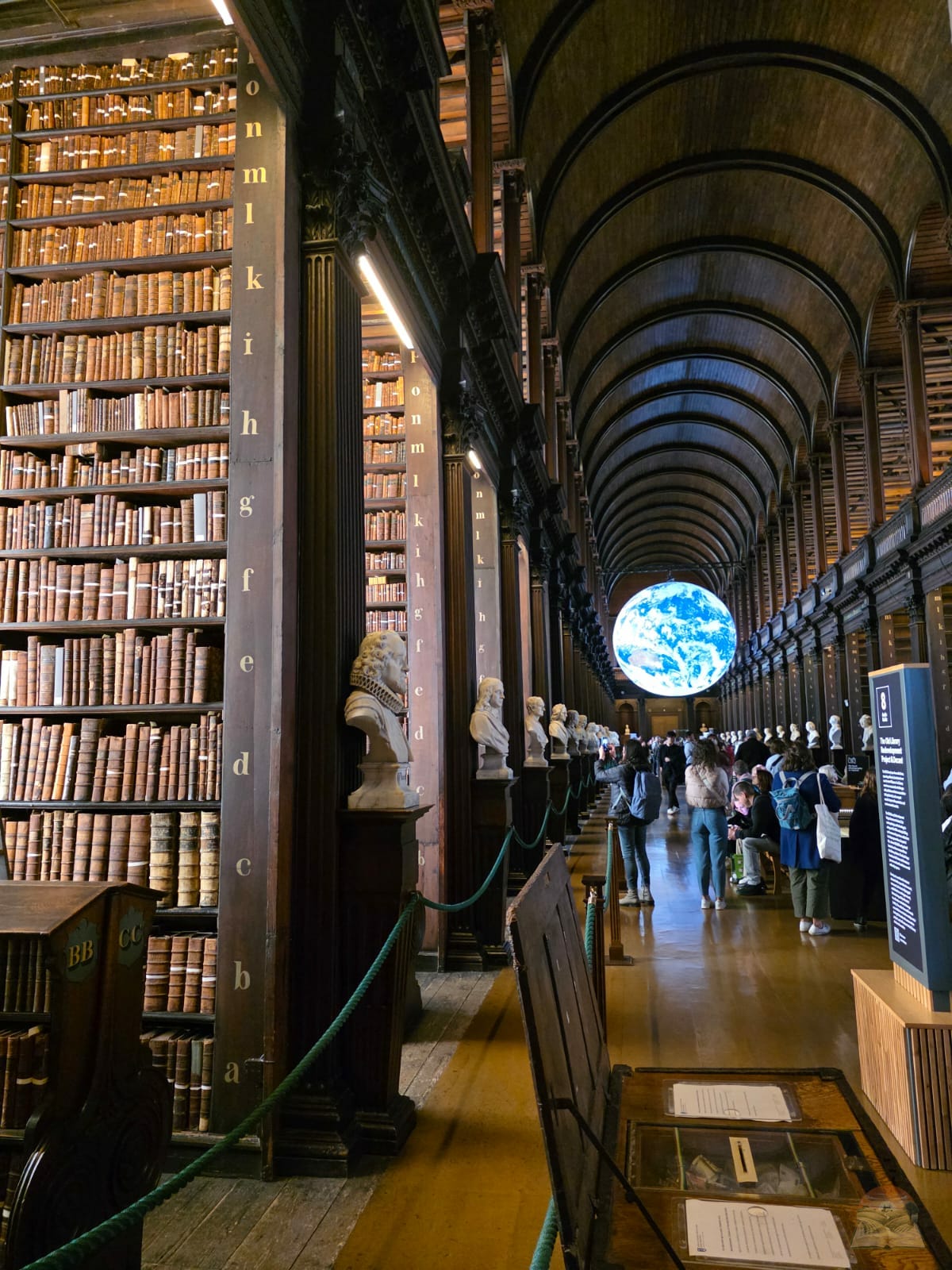

We left the pub and walked across the road to Trinity College, one of the foremost ancient universities in Europe. The beautiful, historic library is open to visitors, with some of its treasures on display. It was a bright, sunny afternoon. Students lay on the neat lawns in front of the buildings, lounging and chatting, whiling away the afternoon in that particularly studenty way we all complain about but secretly envy. A tour of the library cost us €25, which—like everything in Dublin—is a bit pricey, but what an exhibition!

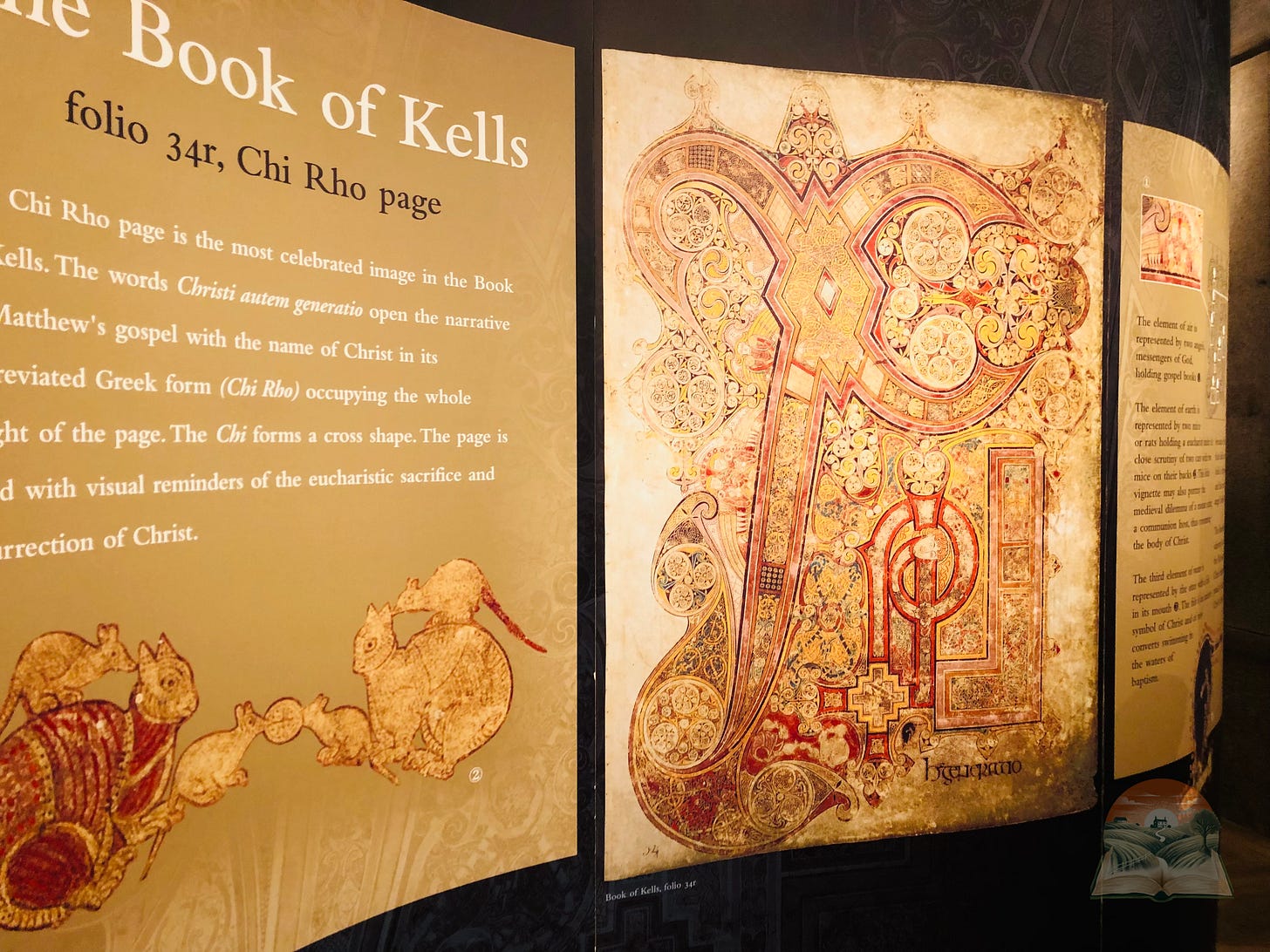

The centrepiece is The Book of Kells: a 9th-century illuminated Gospel and one of the world’s most precious treasures. A room introduces the techniques the monks employed to create such manuscripts: the pigments they used, how they prepared the vellum, and their tireless efforts under the constant threat of attack, plunder, and death. They had sought refuge in Ireland after their original monastery was pillaged by Vikings. The book itself is remarkable, though kept in low light with strict no-photography rules.

The Long Room, where the book is housed, is one of the wonders of the library world: two stories of bookshelves surround a central aisle. There was a globe exhibit, with a slowly rotating model of the Earth spinning above the heads of the watching crowd. I say slowly rotating, although it was going considerably faster than the real thing. I was also impressed to find Brian Boru’s harp on display. This harp isn’t the one that actually belonged to Brian Boru, the 11th-century High King of Ireland, but it is the one that appears on the country’s insignia. There is an interactive exhibition too, with animated facsimiles of the book, talking statues, and film shows telling the story of the manuscript and the library. It is a fantastic exhibition—well worth the entrance fee.

The following day, we explored the Merrion Square part of the city. Oscar Wilde was born and raised here, and you can find tributes to him in the pub, in his childhood home, and in Merrion Square, where a monument depicts him reclining on a rock. Just around the corner is the National Gallery of Ireland—a fine collection of Renaissance and modern art, and the National Portrait Collection, where you can see Ireland’s famous authors alongside celebrities and sports stars. The famous portrait of Yeats by his father is there, as are portraits of Brian Friel, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney and, of course, James Joyce, though his likeness appears all over the city. George Bernard Shaw features prominently in the collection; he was greatly influenced by the gallery and left one third of his estate to it.

The gallery is part of a cluster of buildings that includes the Archaeological Museum and the Library, which was our next stop. Although you can’t enter the reading rooms without a pass, there is a public exhibition about W.B. Yeats. Packed with books, letters, and belongings, the centrepiece of the exhibition is an audiovisual display in which Yeats’s poems are read by Irish voices—some well-known, others less so. It helped me understand Yeats and his position in Irish literature: a counterpoint to Joyce, who looked outward to world literature and classical mythology. Yeats looked back—to an Irish past steeped in myth and legend.

I left my party, who were in need of tea and a sit-down, and went off in search of Patrick Kavanagh. His statue by the Grand Canal looks contemplatively over the water, just as he liked to do in life. Unfortunately, major restoration works meant the canal path was closed. I couldn’t even see the statue—it had likely been put into storage. I did, however, get to try Toner’s: a beautifully preserved Victorian pub, complete with mahogany and glass snob screens and mementoes from the pub’s past. I had a Guinness and admired them. The pub is notable for being the only one Yeats ever visited. He had a small sherry with St. John Gogarty and left.

I met my friends again at Davy Byrne’s: a pub just off Grafton Street, the main shopping thoroughfare. This pub also features in Ulysses, where Bloom stops for a cheese sandwich and a glass of wine. It was by far the best (of many) pubs I visited during the week. The walls are lined with tributes to Bloom, Molly, and Joyce himself, whose effigy adorns the bar in stone, bronze, and paint. I had another Guinness and a plate of oysters—a wonderful combination.

The following afternoon, after an excellent lunch at a restaurant called Brother Hubbard, we visited the Leprechaun Museum to learn more about Ireland’s mythological past. It was a superb experience: our guide told us stories about Leprechauns, the Fear Dearg, and Banshees. She was an excellent storyteller and brought the myths to life in a highly entertaining way. There was a fantastic bookshop at the end. Emma, a folklore fanatic, pronounced it the highlight of our week.

The next day, Mrs. P opted to stay at the hotel to recuperate. Emma, Matt, and I took the tram to St. Stephen’s Green, a beautiful, expansive park in the heart of the city. Alongside the carefully tended lawns and flower beds is a memorial to W.B. Yeats by Henry Moore and a bronze bust of James Joyce. Plaques throughout the park describe its central role in the Easter Uprising of 1916, when the bandstand and other park buildings were used as temporary medical camps for Irish volunteers. Joyce’s bust faces what was once Newman College, a Jesuit school established by Cardinal Newman, which Joyce attended and which now houses the Museum of Literature Ireland.

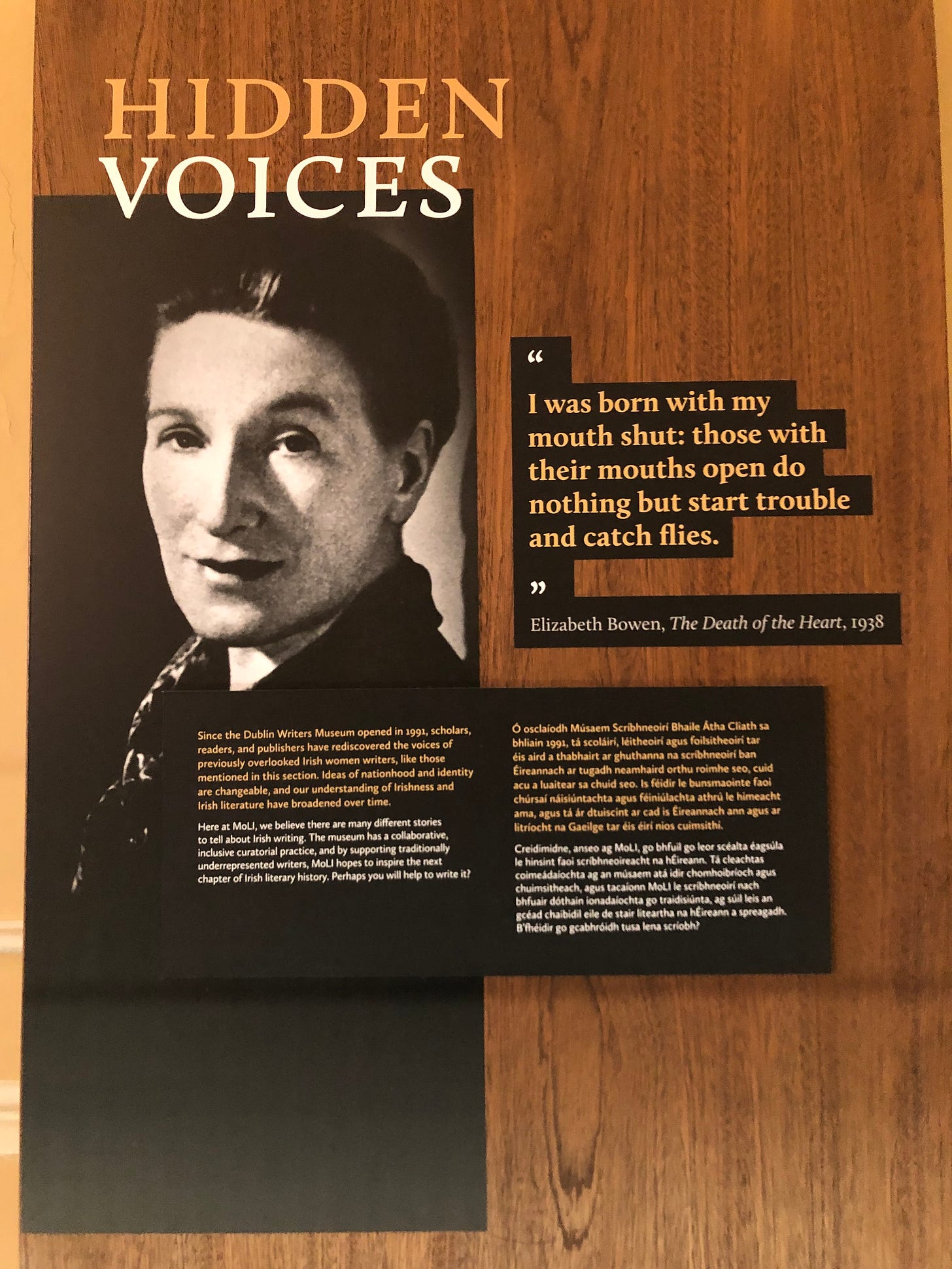

This imaginative museum doesn’t focus solely on Joyce but brings often-overlooked writers—particularly women—into focus, celebrating their contributions to Irish and world literature. There are interactive displays, readings, writing activities, and even video games, allowing visitors to explore Irish literature and its creators. Joyce and Yeats are prominent, of course, but it’s refreshing to see other writers represented and celebrated.

Dublin is famed for its libraries. In addition to the Long Room, Trinity College has the Eavan Boland Library—the only academic library in Ireland named after a woman. There’s also the Chester Beatty Library, featuring printed texts from around the world. We visited Marsh’s Library, an 18th-century library close to the cathedral. I love wandering around old libraries. Being surrounded by books is comforting; I love the smell of old leather and musty paper. We wandered between dusty shelves and admired the huge collection, imagining those who had studied there before us.

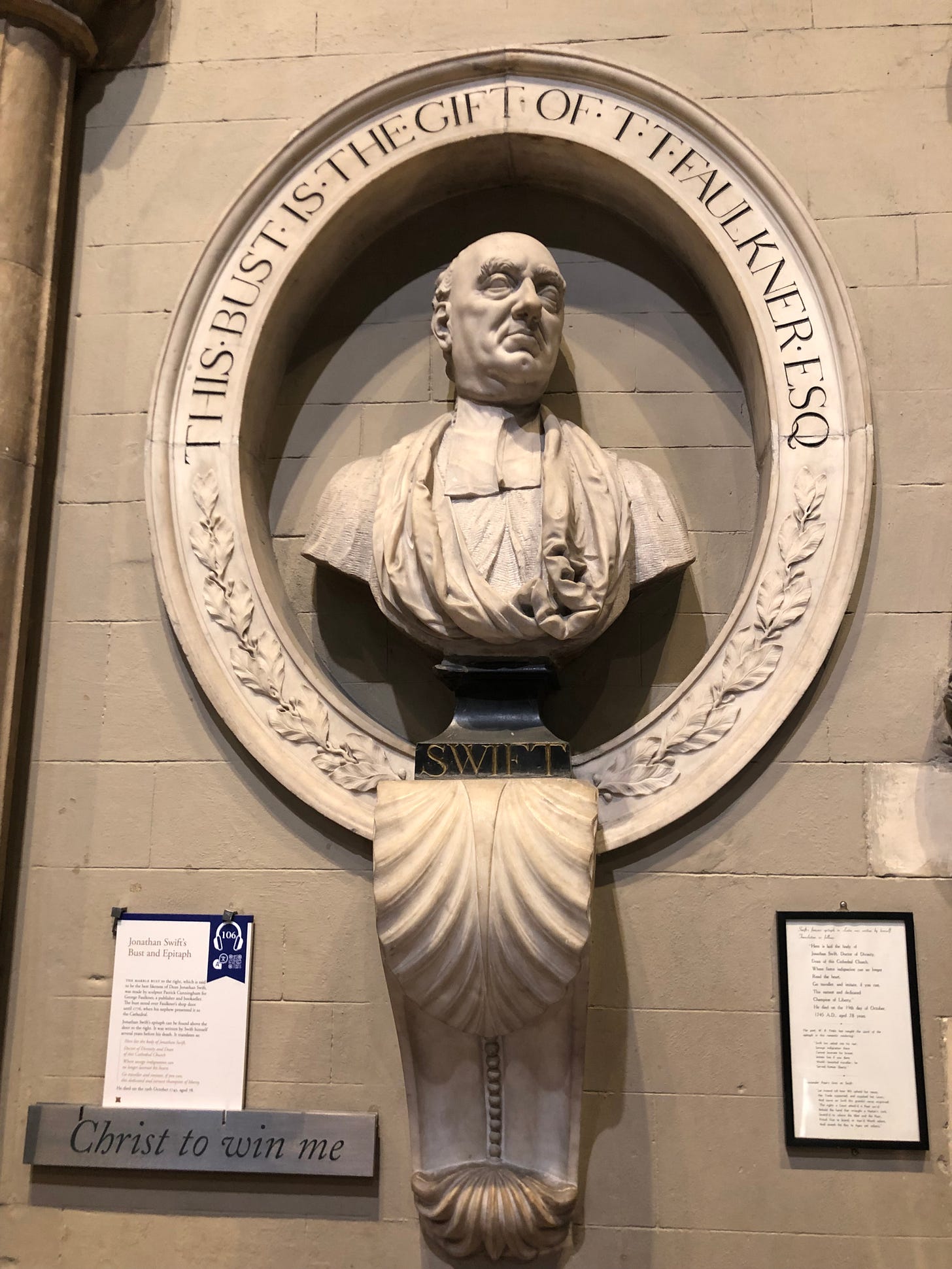

With its soaring arches and intricate tilework, St. Patrick’s Cathedral is a stunning example of Gothic architecture. We came in search of Jonathan Swift, who was appointed Dean of the Cathedral in 1713. His memorial can be found on the south side, near the entrance. Nearby displays offer insight into his life and work, his relationship with Esther Johnson, and artefacts from his time as Dean—including a chalice, snuff box, and books. Swift, born in Dublin and educated at Trinity, became deeply involved in political and religious life. He is most famous for Gulliver’s Travels, a satirical novel examining human nature and society, and for works like A Modest Proposal, in which he used irony to highlight the plight of the poor in Ireland.

Outside the cathedral is another of the city’s fabulous parks. The unseasonably warm weather had brought many Dubliners out to enjoy the sunshine. We strolled along to the sound of cathedral bells. On the east side of the park is the Writers’ Walk: twelve plaques commemorating great Irish writers in alcoves along the park’s edge. We walked through the city back to Bewley’s Oriental Café, where we had afternoon tea and scones in the salubrious surroundings once frequented by generations of Dubliners.

It is a remarkable city—one where literature is celebrated to the point of worship. It was fascinating to discover so many writers, and to celebrate those I’ve known and loved for years.

Leave a comment