I didn’t have very much time to spend in Rugby but I was determined to visit as the little midlands town was home to one of the greatest poets of the 20th Century, along with a great deal more literary history, much of it connected to the large public school that dominates the town.

We had parked in the town centre which didn’t give us a good initial impression of the town: a busy road, soulless mall. A little exploration, however, and I discovered some lovely little back-streets with an array of pleasant buildings. I first headed to the art gallery, with a museum that will tell you all about the Roman development of the town. Sadly, not fully open and a reminder that we are still living in the midst of a pandemic. There is also a Webb-Ellis Museum, celebrating the town’s links with the sport. Rugby dominates the town, references to the sport and the name ‘Webb-Ellis’ are everywhere: pubs, cafés, shops and streets reference the game’s origins. For those of you unfamiliar with the story: in 1823, during a school football match, William Webb Ellis, standing beneath a particularly high ball, caught it in his arms. Rather than place the ball on the ground for the opposing team to free kick, he ran with it, taking it into the goal. The story has passed into legend but, nevertheless, the version of football played at Rugby School had enough variations to warrant its development into a distinct sport.

This story has always been somewhat controversial. Thomas Hughes, author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, was asked to comment on the veracity of the myth. It emerged that Webb-Ellis, far from being an inventive player, was someone who would go to any lengths to gain an advantage. It seems to be part of a tradition in this country that privileged young men can bend rules to their own advantage and get away with it. Thankfully, we’re no longer ruled by people with this attitude; can you imagine the mess they’d get us into?

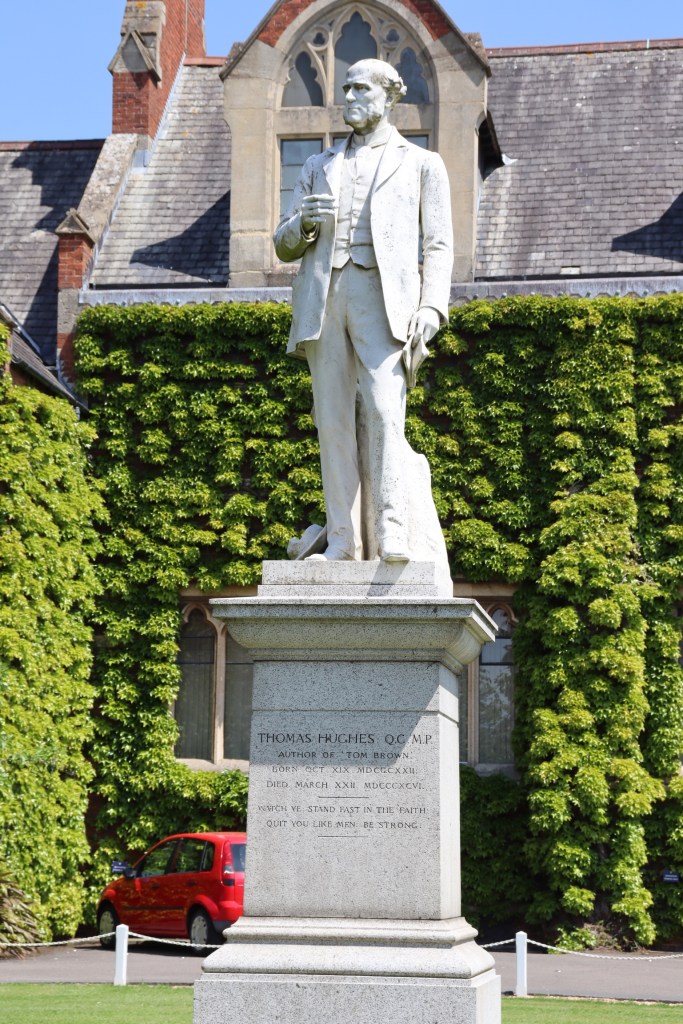

Thomas Hughes was an interesting character. He was a Liberal MP and something of a reformer. His sister, Jane Senior, was the first female Civil Servant and instrumental in forging worker rights for domestic servants. His most famous novel, Tom Brown’s Schooldays, was based on his own experiences at the school, which he attended from 1834 to 1842. There is a statue of him in front of one of the school buildings, standing stoically, his finger marking the page of a book he holds in his hand, as if he has been taken by surprise while doing some reading. The book seems to have enjoyed a remarkably long life span: influencing many subsequent school stories and remaining popular enough to made into a film as recently as 2005.

The school has a museum, which is opened at limited times. They have a number of artefacts relating to famous alumni and more about the establishment of the sport, which they seem to be most proud of. Here you can find out about some of the school’s other literary Rugbeians, a startlingly impressive list, which includes: Arthur Hugh Clough, Matthew Arnold, Lewis Carroll, Arthur Ransome, Salman Rushdie and Anthony Horowitz. The museum was closed on the day I visited, however. School museums are often only open during term time, so it’s difficult for me to get to see them. The school gates where shut and I could see no sign of it.

Rugby’s other famous son is quietly commemorated throughout, embraced equally by gown and town. Rupert Brooke was born in Rugby in 1887. His father was a teacher at Rugby school and his mother was school matron. His birthplace is a fine Victorian villa, comfortable middle-class dwelling, red brick with gleaming white stone lintels and ornate bargeboards. Brooke had a successful career at Rugby, developing romantic relationships and verse styles alike. He went to Cambridge in 1906, and would go on to become acquainted with the hugely influential Bloomsbury Group: the group of writers, artists and progressive thinkers that included Virginia Woolf and EM Forster.

Brooke joined the Navy on the outbreak of war and his tragically short life ended on Skyros en route to Gallipoli in 1915, when he succumbed to septicaemia caused by an infected mosquito bite. His poetry, having been written early in the war, is nostalgic, patriotic and idealistic; there is less despair that that of the later war poets, who had witnessed the full horrors of war. Read The Soldier and you’ll see what I mean.

There is a statue to Brooke in the towncentre. He stands in contemplative mood in a little park, sun dappled and leafy, the trees giving some welcome patches of shade on this warm spring afternoon and a lovely spot in which to sit for a few minutes.

There is a memorial to Rupert Brooke in a cemetery just outside the town, so I toddled off there to take a look for it. It took me a good while searching but I eventually found it. His grave is in Skyros and was, until an ornate marble tomb was built there, marked with a simple white wooden cross. When the tomb was erected, the simple cross was brought back to England and placed on the family grave site. Recently, this became so weathered and damaged that there were fears for its future. The marker was moved to the safekeeping of the school chapel and the stone memorial you can see today took its place.

Memorial found, there was nothing to keep us in the handsome midlands town. The hour was now late and Mrs. P. and I wended our weary way homeward. After tea, of course. We’re not complete savages.

Leave a comment